The employer’s challenge in an AI workplace

Cost-cutting, staff anxiety, and the need for human judgment

The promise and the lag

It’s an open secret that nearly every employer is desperate to cut costs using AI. While no job is safe from AI, junior jobs are at most immediate risk. But, there is an inevitable lag between tech moguls developing the basic albeit very sophisticated tools, and the development of tools actually suited to their tasks.

Flying cars and AI infrastructure

There are lots of metaphors we could use for this process, but the easiest is flying cars which have been foreshadowed for decades. The technology permitting flight has been available for a century. Helicopters, three quarters of a century. But do we have flying cars? No. We have aeroplanes for long distance travel, we have drones for limited consumer delivery purposes – and modern warfare. We’re narrowing in, but even flying taxis remain a promise. What’s holding us back? My best guess is energy, safety, and infrastructure.

Energy, safety, and systems change

All three are mirrored in AI. Energy’s already shown itself as a problem. So is safety, with AI capable of doing almost anything that anyone sensible wouldn’t want. But, for the workforce the vital topic is the one which concerns systems change, infrastructure.

Ranking the threats to jobs

People used to hold conferences about the “Future of Work”. The futility of that type of thinking is highlighted by AI, and it would be only an invitation to be subsequently proved wrong to try to guess at what work will look like in the future. However, it’s easier to provide a ranking of the threats from AI to existing jobs.

1. Process-oriented jobs

First against the wall? Process-oriented jobs. Supermarkets have provided us with psychological preparation for this shift. Ever-improving tech has not just permitted self-checkout, but it permits self-checkout which is ever better directed to preventing theft through positive and negative checks. The loitering assistant? The overseer of the tech.

So what do these process-oriented jobs look like? They can be almost anything. They can be your conversation with the bank to tell them that you will be travelling overseas, they can be the anti-money laundering checks when you sign up for a new bank account, they can be almost any internal corporate or government-mandated system. They are rules-based systems which conclude with a specific action or actions.

Tech companies are selling solutions which are directed to eliminating these jobs. Perhaps the most consumer-facing ones are in the form of the AI-enhancement of chatbots on websites. Once a person (possibly in some far-off land) tapped replies into the textbox after asking if you’d like to know about the latest cars for sale. Then, they became more sophisticated with “canned replies” and logic chains which reduced the need for human involvement. Now we are seeing offerings which offer to resolve IT issues, make changes in banking databases and issue new cards, or even run full information gathering or giving sales conversations entirely by reference to a dataset and lead qualification questions. No human required.

2. Analysis-based jobs

Also imminently replaceable are analysis-based jobs which are inherently repetitive. Easy examples are in medical diagnosis. While GPs and specialist doctors may generally be pretty safe for now, radiologists for instance might need to think twice about what they are doing with their time. Big datasets of scans facilitate diagnosis. Where this thinking reaches its limits though is where the possible sources of relevant information for decision-making are too disparate and the available methods of reasoning too numerous.

Roles that remain

While I say that rules-based and repetitive analysis roles are going if not already gone, this does not mean that every role evaporates. In fact, the roles which remain provide important clues for the jobs which are up the value chain where employees are getting nervous. First, I suggested the supermarket tech needs an overseer. Well, actually, in the supermarket ecosystem the overseer is equally fulfilling the performative function of keeping the customers in line and preventing out-and-out theft. But, it is true that AI-based solutions need to be monitored. We have all heard about hallucination and the need for training on datasets, which must give us all a little fear that the tech could easily get up to something naughty. More importantly, when we adopt what’s ultimately a statistically-based analysis, there are going to be situations where things go wrong. I don’t want to be the victim of the AI-radiologist missing the massive tumour in my chest. Nor do I want to be the person who is denied a new bank account because the system confused me with a sanctioned Russian-oligarch.

Role one: the game-keeper

Role one is the game-keeper. No Australian who can remember Robodebt will sensibly accept a system which is an unmonitored function of AI, at least for now. So, we would come to expect that a single radiologist could oversee a great deal more diagnosis aided by an initial AI analysis. Similarly, we would expect that a single highly-trained consumer service representative could manage the fractional number of ‘exceptions’ where the chatbot yields an unexpected outcome. By way of career-development, transitioning to game-keeper presents a path forward.

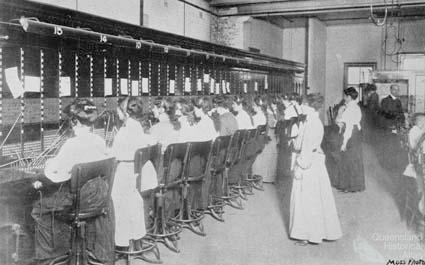

Role two: the telephonist

Role two exists in anticipation of the customised role-replacing solution. It’s the job at the manual telephone exchange, connecting inputs and outputs. It’s applicable to both process-oriented jobs and the more impressive-sounding jobs which often require critical thought. The regular commercial solutions offer apparent efficiencies in these roles if:

i. You have the necessary data;

ii. You can frame the necessary questions; and

iii. You can identify if the output is up to snuff.

In other words, if you understand the process and know what the result should look like, then AI can work for you. If you fail on any of these fronts you are at risk of answering the wrong question, producing work which is insufficient, incomplete or is based on hypothesised facts, or which simply isn’t good enough.

Why humans are still required

For now, each of these roles are safely in the territory of “human required”. Each requires knowledge of (i) relevant systems be they internal corporate systems, legal systems or even political systems or the way in which society works; (ii) background knowledge relevant to the work; (iii) an understanding of what ‘good’ (and ‘bad’) looks like; (iv) an ability to think laterally; (v) the ability to write and communicate; and (vi) critically, an ability to do the work yourself. There can be no expectation that you would do the work as fast as the machine or that you would even want to do the work that you are asking the AI to perform, but you need to be able to spot the clause missing from the contract or the obvious fallacy in the letter.

A perplexing aspect of both the game-keeper and manual telephone exchange roles is that you need to keep your hand in to be able to do the work. A study on gastroenterologists suggests that the greater your reliance on AI, the rustier your skills get. In fact, the authors of the study to be published in the October 2025 issue of The Lancet Gastroenterology and Hepatology found a significant reduction in polyp detection. They hypothesise that: “[w]e assume that continuous exposure to decision support systems such as AI might lead to the natural human tendency to over-rely on their recommendations, leading to clinicians becoming less motivated, less focused, and less responsible when making cognitive decisions without AI assistance.”

Consequences for employees

This all has consequences for both employees and their employers. For the employee there’s anxiety. For the employer, a raft of employees quitting ostensibly to focus on their health and wellbeing before AI is anywhere near capable of taking their roles is a problem. No workforce equals no business. Fleeing an inevitable change too early might seem smart, but where’s the employee going to feel safe? Well, there’s plenty of need for competent workers in aged-care and teaching, but lots of office workers are going to find those options unpalatable.

Consequences for employers

Ultimately, for the employer, there’s a need for in-house coaching:

i. At a leadership level to develop the plan for creating game-keepers and, for the foreseeable future, highly-skilled manual telephone exchange workers. This is the path to productivity. Equally, leaders need to be looking at how they create the off-ramps for employees who are no-longer needed. The prospect of structural unemployment without support to move into the next role is not a recipe for retaining staff in a time of transition. Communicating policy to support transitioning staff early (and being believed) will be key to retention; and

ii. At an employee level, creating the systems and training for high-level performance, cognisant of the higher-level analysis needs where more and more work is capable of being performed by AI.

Policy and training

If you want to discuss policy development and internal training in your organisation, please contact Loosemore Advisory at [email protected].